President Lai Ching-te introduced T-Dome, Taiwan’s new multi-layered air and missile defense architecture designed to withstand massed drone attacks, cruise missiles and ballistic threats. Lai framed the initiative as a practical, munitions-centric defense strategy rather than a literal protective bubble, stressing that magazine depth, integration and industrial sustainment will determine how long Taiwan can endure sustained coercion. He also indicated plans to phase funding increases across upcoming budgets.

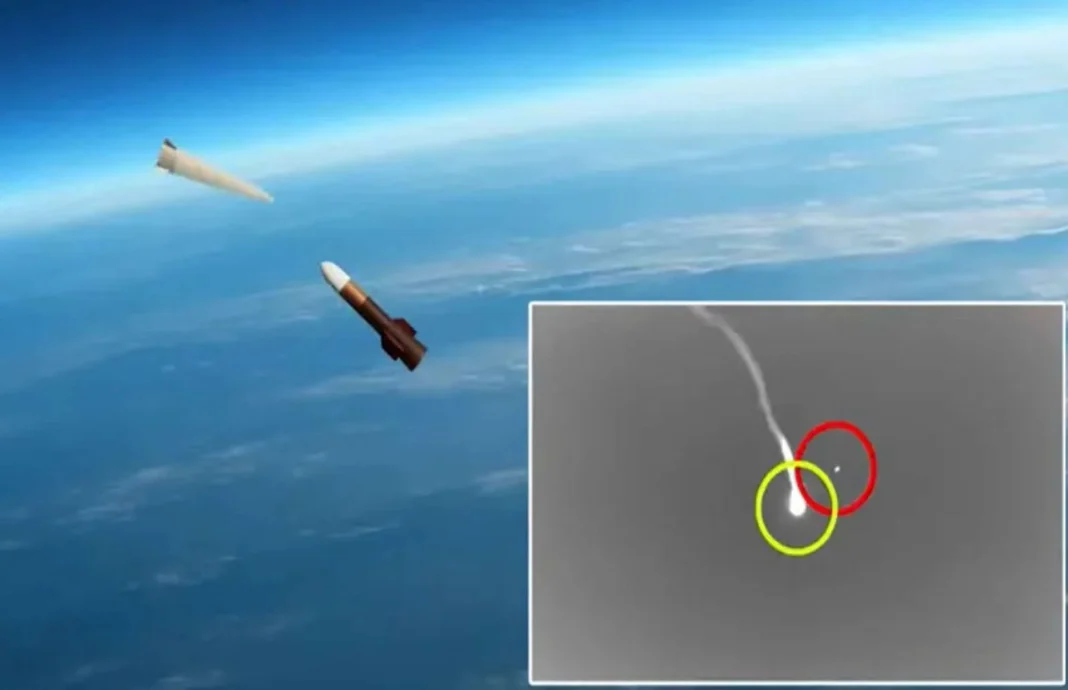

At the high end, T-Dome centers on a domestic interceptor family commonly referred to as Chiang Kung, which is evolving toward capabilities similar to a higher-reach, high-energy interceptor. These designs use two-stage motors and modern active-radar seekers to engage medium-altitude ballistic threats and high-flying cruise missiles at engagement ceilings that exceed traditional Patriot envelopes.

Complementing indigenous interceptors, Taiwan retains Patriot (PAC-3 MSE) and Sky Bow batteries as foundational layers. PAC-3 MSE improves terminal maneuverability against sophisticated targets, while Sky Bow III provides a reloadable, home-grown magazine that reduces reliance on foreign supply chains. These systems are intended to operate distributed and networked from hardened positions to complicate an adversary’s targeting.

The mid layer adds substantial density and flexibility. NASAMS paired with AMRAAM-ER offers mobile, concealable launch options that separate sensors and shooters by tens of kilometers, reducing the risk a single strike will degrade both detection and engagement capability. Containerized launch rails and common missile family logististics simplify reloading and training.

Short-range defenses include truck-launched Antelope (TC-1) interceptors and 35 mm gun systems using programmable AHEAD rounds—effective counters to low, slow drones and rocket artillery. These units are tasked with protecting critical infrastructure where cost per engagement and sustained firing rates are decisive.

T-Dome relies on a tighter command network that fuses long-range early-warning radars, mobile 3-D sensors, passive detectors and each battery’s fire control. The concept anticipates AI-assisted classification and automatic handoffs, so a high-altitude interceptor engagement can prompt immediate follow-on shots from Patriot or NASAMS if a threat persists—reducing human decision latency and limiting wasted interceptors.

Conceptually, T-Dome differs from Israel’s Iron Dome. Rather than a single product optimized for rockets, Taipei is building a vertically integrated stack spanning heavy exo-atmospheric interceptors down through medium-range AMRAAM-ER and finally to guns and very short-range missiles, all tied together by a national command web—more akin to the multi-layer posture the U.S. is assembling for Guam than a single-system solution.

Given regular PLA drills and the prospect of saturation attacks in early crisis days, T-Dome’s value is in dispersing risk, multiplying magazine depth and keeping decision cycles tight. The program’s long-term success depends on industrial throughput: interceptors, spares and trained crews must be replaced faster than threats can be regenerated. Lai’s budgetary signal is therefore as important as the technology itself—sustained stocks and logistics make the dome a lasting defensive capability rather than a temporary shield.